This guest post by Bill Sasser was originally published in Raw Vision #115 and on billsasser.com. Posted here with permission.

“Have you ever seen a whale?” Herbert Kearney asks perched on a stool in his huge post-industrial art space, just downriver from New Orleans’s French Quarter. “I’ve seen a whale, a big whale, off Alaska. Seeing it you realize we aren’t alone in the universe, big monster fins are skimming under the surface. That big eye looking back at you, it’s the biggest soul in the world. They’re beautiful creatures.”

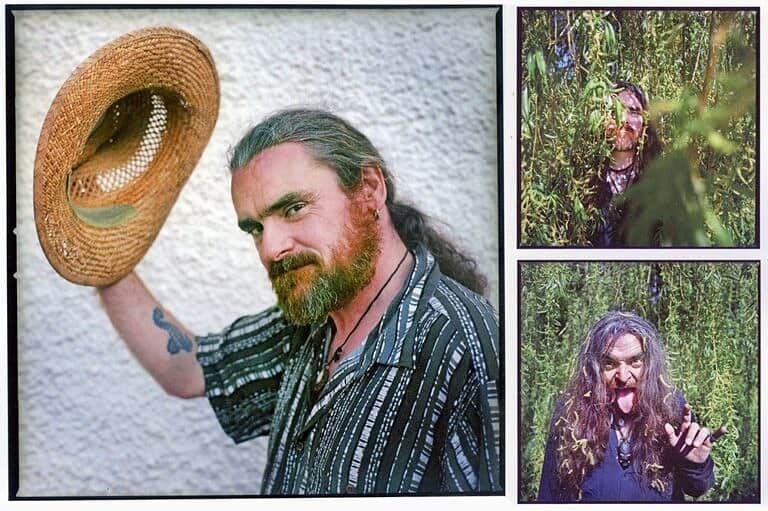

Just sitting still, Kearney emanates a halo of manic energy. Hennaed hair twisted back in a bun, he wears a wool coat, hat, and gloves—February 2005 is cold and the old hosiery mill is unheated.

A sculptor, painter, and poet who had spent a decade and a half traveling the world, he had arrived two years earlier and found a permanent spiritual home, in a port city where the creative slipstream welcomes newcomers, and art lives in the streets.

A wild Irishman with a contagious love of life, he was also a constant seeker, says Bobby Yarra, a longtime friend and patron. A former attorney who lives in northern California, Yarra met the artist in New York City soon after he arrived in the U.S.

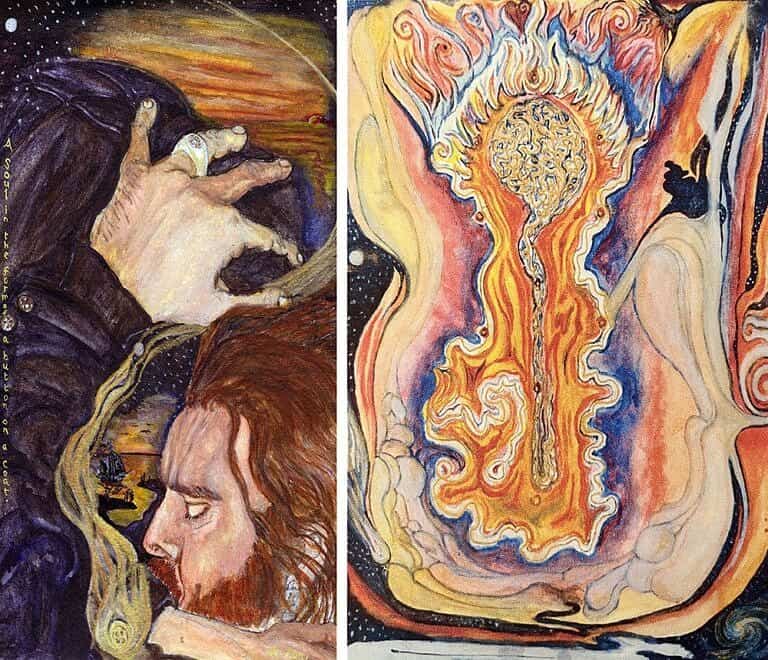

“Herbie was a self-taught student of Eastern spirituality and the ancient mysticisms of The Golden Bough, and found much inspiration in the undercurrents that run deep in New Orleans,” Yarra says. “Symbol-making was part of his everyday life. He also claimed to see the energy auras of people he knew.”

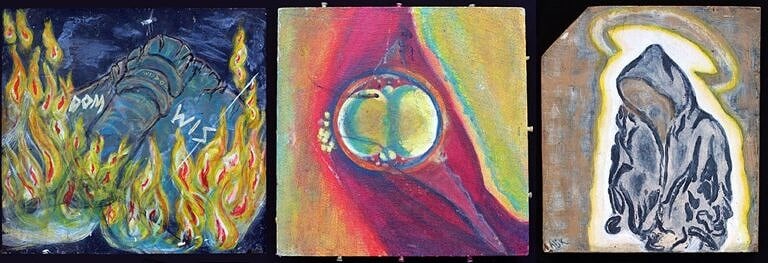

Ron’s Shape (watercolor painting from Barbaric Haiku), 2002, 8×12 in.

Kearney died in 2021, age 58, in the final month of New Orleans’ covid lockdowns, leaving behind troves of artwork that could be a metaphysical autobiography. Often underappreciated by gallerists and curators, perhaps his most striking art was his own life, and the studio living spaces that were his ever-evolving, visionary installations.

A native of Cork, Ireland, he won a green card to immigrate to the U.S. in 1986, through a new visa lottery program. A year later, after quitting art school, he arrived in New York City at age 19 and found a job driving horse carriages in Central Park. A co-worker introduced him to Vali Meyers, the Australian-born artist and muse to the Beat Generation, who lived at the famed Chelsea Hotel. He soon moved in with Myers. At the Chelsea, his friends and acquaintances included Beat poet Gregory Corso, avant-garde photographer Ira Cohen, and New Wave luminaries Patti Smith and Deborah Harry.

“Herbie was in with the most hip, creative crowd you could imagine, including the outcasts and criminals,” says Yarra, who spent much time at the Chelsea. “He was so good looking back then, and had such a gift for Irish blarney. No one was more fun to be with.”

When Meyers moved back to Australia, Kearney stayed on the East Coast, working as a commercial fisherman. With no proper studio, he took up the ancient Celtic art of bone carving, working with a pocket knife. When Myers needed help building a new studio, he hitchhiked across the U.S. with $50 dollars in his pocket, and crewed on fishing boats off Alaska before flying to Melbourne. He continued with bone carving and staged some noted gallery exhibits, but the old sailor’s pastime once landed him into the custody of the U.S. Immigration & Naturalization Service.

“He flew back with sharp bone carvings in his bag, and he was this madcap Irishman, which they didn’t like, so they locked him up despite his papers being in order,” recalls Tasha Robbins, Kearney’s longtime life partner. “He never got his bones back.” Yarra, an immigration lawyer, worked for three weeks to get him out. Kearney joined him in California, where he soon met Robbins. The artist moved into her storefront art studio in San Francisco, and began painting and sculpting in earnest.

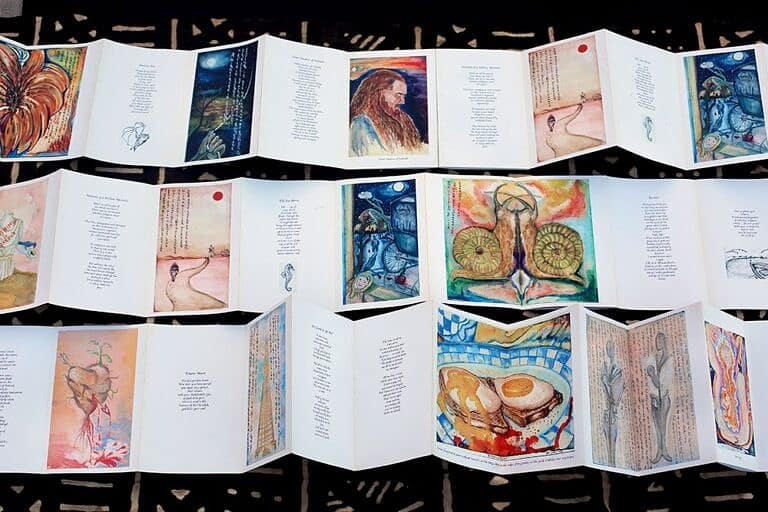

Immersed in the North Beach poetry scene, Kearney created a poetry book, Barbaric Haiku, designed like a Japanese-style accordion notebook. Illustrated with his watercolors, he spent months constructing hundreds of copies. Jack Hirshman, the Poet Laureate of San Francisco, read at his opening.

Rising rents prompted the couple’s move to New Orleans in 2003. Kearney continued his summertime trips home to Ireland, where he worked on a four-ton section of century-old macrocarpe pine that he’d installed in his father’s backyard. The sculpture The Death of Ferdia was inspired by the legend of the Milk Brothers, a tragic Celtic myth of brother killing brother.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

“Our mother was a great teller of the old stories, and Herbie immersed himself in that at an early age,” recalls his sister, Ruth Mackey. “When he found the fallen pine tree on his uncle’s farm, he immediately had a vision of what it could be.”

In 2005, Kearney and Robbins evacuated from New Orleans just before Hurricane Katrina. He returned within weeks to rebuild his life, and his studio. Several of his paintings were included in a show of hurricane damaged art at the city’s Contemporary Arts Center. David Rubin, former curator, remembers the time before and after the storm, before gentrification began in earnest, as a creative high note for New Orleans.

“Weekends were filled with openings, and artists felt a great freedom to be original. The joy of it was contagious and Herbie fit in like an instant local denizen. He rode that wave, then was right back after the storm to rebuild.”

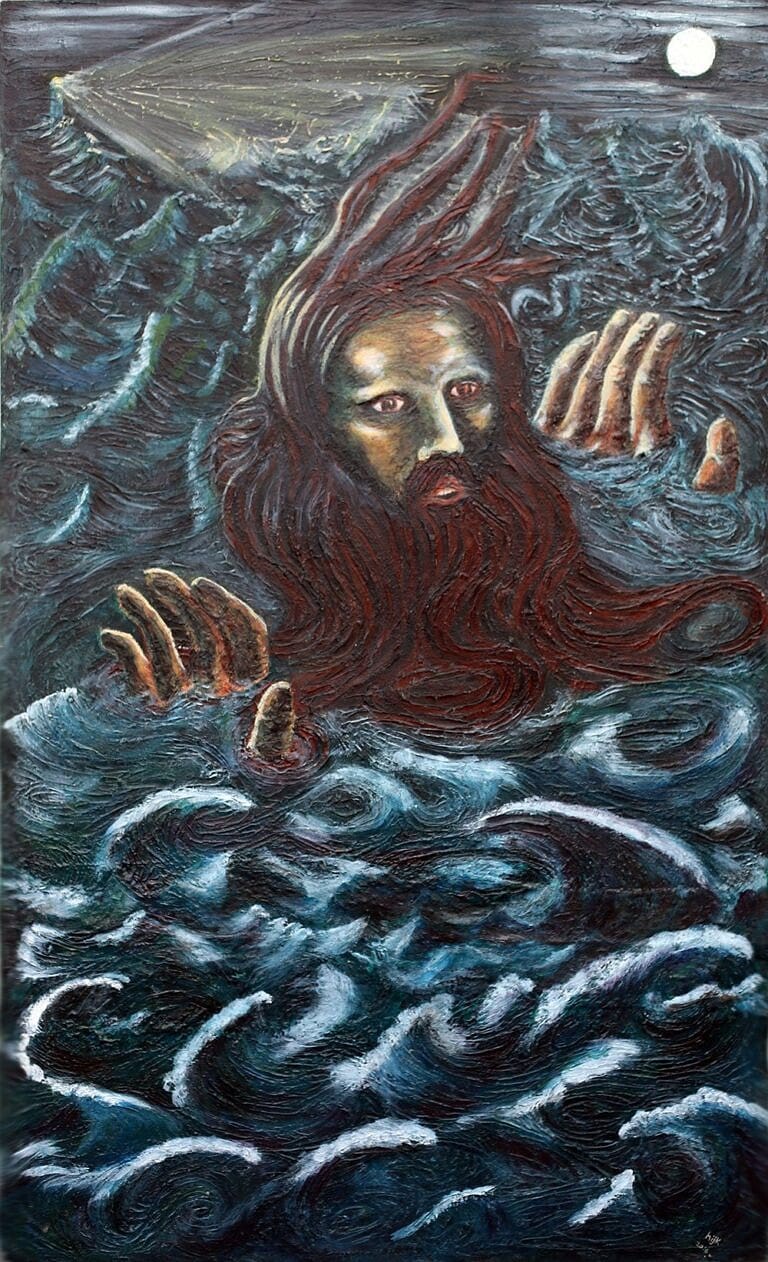

After Katrina, boats and water would figure much in his art, the cause of rebuilding New Orleans a heartfelt inspiration. In his wrecked studio, he did a quick charcoal drawing of a wild, bearded man lost in a tempest. The study led to an ambitious self-portrait in oil, Man Treading Water, with Kearney as a metaphorical seaman lost in dense, textured waves. He painted for two years before calling it done.

Conjuring the time and place of Katrina, for other pieces he used materials collected on the streets. “All Mothers Are Boats,” his sculpture of a wrecked fishing boat, was made from scraps found along the Mississippi River and curbsides near his studio. Methodically improvising, he reworked the sculpture for years, at one point adding his own blood to the piece after accidentally cutting himself.

Another piece, Quan Yin: Rebirth, offers the Buddhist goddess of mercy as an avatar of regeneration. Constructed on canvas stretched on a driftwood frame, the sculpture was made with glued fabric, found objects, and homemade plaster, unified with numerous layers of paint.

In 2008, Kearney and collaborators staged a “guerilla art drop” after failing to win inclusion in Prospect 1, a citywide art biennial. Designed by Kearney, the artists installed a 20 foot-tall sculpture on a prominently located vacant lot just before the opening. Renavus is equal parts Viking ship, shamanic offering, and mythical winged creature, and 15 years later, the only vestige of Prospect 1 still on display in the city.

Quan Yin: Rebirth, mixed media, 2008.

During his years in New Orleans, he joined dozens of other New Orleans artists living in shuttered factory spaces, on the down-low due to health and safety regulations. His studios were crammed full of large paintings, huge sculptures, and totemic objects that he found on the streets, giving his spaces the feel of voodoo altars or magic Cornell boxes at warehouse scale.

Kearney’s persona shifted easily between self-taught holy man and comic surrealist in bohemian dishabille. As with other visionaries, he perhaps too often sought inspiration through alcohol, drugs, and extremes of experience. Determined to quit drinking and smoking, he returned to New York in 2010 for underground treatments using ibogaine, a powerful hallucinogen from Africa, which tapped unconscious connections. Afterwards he became fascinated with “sacred geometry,” the metaphysics of three dimensional geometric shapes.

“He saw other things on ibogaine,” Robbins remembers. “One of them was The Blue Lady, who told him wise things, and he did a great painting about her.”

Back in New Orleans, he stayed sober, but the artist’s life took a dark turn when he was assaulted by a street tough along the Mississippi riverfront, at a spot where he’d spent many sunsets meditating and doing yoga. “Herbie suffered a severe head injury, and wasn’t the same after that,” Yarra says, recalling migraines that never went away. “His joie de vivre was taken away.”

After losing his longtime studio to gentrification, he moved into a former brewery by a railroad junction. The property included an empty 60 foot-tall concrete grain silo, which he soon put to use. Exploring sacred geometry for a group art show, Kearney constructed colorful hexagonal sculptures from plastic piping, which he installed with lights in the top of the silo. At the bottom, he built a saltwater sensory deprivation tank, where he would mediate in complete darkness for up to 36 hours at a time. He recalled entering what seemed another dimension, where he silently conversed with otherworldly beings composed of jewels and quartz.

“At one point I felt myself leaving my body, leaving this world, then I wasn’t ready to go yet,” he recalled. “They said okay and went on their way, then I got out of the tank.” In his fifties, Kearney had the face of a man who’d long wrestled with the world and himself. Still searching, he started drinking again. People gave him esoteric books to add to his huge collection, but sometimes what he really needed was a good meal.

In 2017, he returned to Cork to care for his elderly father. After nearly 20 years of intermittent work on the monumental sculpture in his dad’s backyard, he finally completed it during covid lockdowns in 2020. The Death of Ferdia is now on permanent display at Kearney’s preparatory school alma mater in Cork, Presentation Brothers College.

The artist had returned to New Orleans and was living with friends, in sight of the Mississippi River when, just a month later, he died of a heart attack. The Mayor offered condolences following Kearney’s death, as well as those of three other well known New Orleans artists, who all passed during the final month of the city’s pandemic quarantine.

While far away from home, his family feels it right that he spent his last days in the Louisiana city. “Herbie found his own people in New Orleans,” says his sister Mackey. “After Katrina, he was determined to stay and rebuild, and after several years in Ireland, he was just as determined to go back again.”